Donald Trump wants to stop participating in the UNFCCC process and pretend he is not sworn to uphold its provisions. That is all.

On January 7, 2026, Donald Trump issued an executive memorandum purporting to “withdraw” the United States from 66 international organizations and treaty processes. The President can, with executive orders and memoranda, provide instructions to federal agencies, regarding matters of policy and how best to implement written law; he cannot, however, void ratified treaties or unilaterally override acts of Congress or determine by himself what is “in the nation’s interest”.

With specific regard to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC or the Convention), Article 25 allows nations that are formally parties to the Convention to withdraw “at any time”, with that withdrawal taking legal effect one year after the notice of withdrawal is received. Article 25 does not, however, override Article VI of the Constitution of the United States, which specifies that a ratified treaty is “the supreme Law of the Land”, i.e. part of the Constitution itself.

A ratified treaty sits above the authority of the President, the Congress, or the Courts. None of them can unilaterally cancel a ratified treaty. There are several important reasons this has not been tested, historically:

- Most elected officials are not interested in degrading the nation’s international standing and credibility by making clear that commitments mean nothing;

- The process for removing a ratified treaty from the body of constitutional law would be complex, uncertain, and might require a formal amendment to the Constitution or a process similar to an amendment—which could require a vote of at least two-thirds in both houses of Congress;

- The reasons for that are that backing out of treaty obligations degrades the nation’s international standing and credibility, which can degrade trade relations, financial and fiscal stability, and national security;

- The President cannot simply make any decision he or she wants; only those specific authorities written into law can be exercised by the Executive, and then only within the boundaries of all other applicable laws.

The President does not have legal authority to unilaterally void a treaty ratification. No such authority exists. Where it has been treated as normative historically, that fact is due simply to Congressional inaction. In reality, such cases entail breach of both the treaty commitments and the Constitution’s own constraints on the unilateral use of executive authority.

Given the clear language of Article VI, the only recognizable legal process for full repeal of a ratified treaty is the process that would amend the Constitution itself. According to Article V of the Constitution, a vote in favor by two-thirds of both the House of Representatives and the Senate, each in their own right, would be needed to trigger the lawful removal of a ratified treaty from the body of Constitutional law.

No political math allows for a scenario like that playing out to eliminate the 1992 Climate Convention. Nearly all other existing treaties would face the same hurdle. In principle, a joint resolution passed with 2/3 support in both chambers could include a reform process aimed at empowering the President to seek renegotiation, but treaties are not made to be unilaterally reformed.

What this means in practice is that the President’s assertion of this power is legally nonsensical and nonbinding. He is, effectively, attempting to use his power as the chief administrator of the federal administrative state to direct federal agencies to cease participation in and consideration of the terms of specific treaties and conventions. In most cases, this will likely entail a temporary withdrawal of funding and staff time, which might or might not be overridden by Congress.

Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution of the United States specifies: “the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.” This provision could allow Congress to order that specific functions be funded and staffed and direct heads of departments to properly staff those functions according to agreed terms of law, including existing ratified treaties.

Interestingly, President Trump seems to acknowledge this in the same document purporting to have this sweeping authority given nowhere in written law. In Section 1(c) of the January 7 memorandum, the President specifies “For United Nations entities, withdrawal means ceasing participation in or funding to those entities to the extent permitted by law.”

This means:

- If Congress has required funds be allocated, those funds must be spent as ordered.

- If a treaty is ratified and as such forms part of the body of US Constitutional law, it is not undone by this document, because there is no lawful way for that to happen.

- Trump is testing the will of Congress, the Courts, the States, and the People, to demand compliance and implementation, though the President opposes it.

- Any future President can unilaterally order the reversal of this memorandum, because it does not formally end any treaty obligations.

Regardless of President Trump’s actions or desires, the letter of the Convention not only stands; it stands as US Constitutional law. States may, as they have in the past, step forward not as parties to the Convention but as implementers. There is nothing in the Convention that contravenes any part of the Constitution, and implementation is a solid, value-building economic development strategy.

States and cities that lead will be rewarded by investors and by the innovation economies that spring up around forward-looking climate policy. They will also be better positioned to avoid the catastrophic costs of the pollution economy and unchecked climate disruption.

Even states whose voters supported President Trump’s election by wide margins, and which depend on fossil fuel extraction, transit, or refinement for revenues, can improve their economic futures by participating in the innovation and sustainable investment boom that comes with UNFCCC implementation. Voters will be loathe to see their local and state leaders forego these opportunities and condemn their local economies to outdated, unwieldy, and unjustifiably expensive polluting practices.

The U.S. has not “left” the UNFCCC, though Donald Trump might decline to send negotiators to ensure U.S. views are heard and included in the future of global economic cooperation, trade, and finance. Beyond that, there is no genuine legal or practical reason for doing so:

- In technical terms, it should be possible for polluting industries, including the producers of combustible fuels, to develop zero-pollution systems.

- The use of public power to advantage a polluting industry, which generates widespread harm and cost to others, over a clean industry which does not, is obviously illegitimate.

- The Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice affirmed that the duty of governments to act against climate change is inherent in human rights.

- As such, the overall structure, purpose, cooperative negotiated process, and country by country standard of the UNFCCC could not be better for the US.

It is up to the states to use their 10th Amendment authority and Congress to determine whether its Article II, Section 2 authority should be invoked. The 2026 budget negotiations will determine what funds Congress allocates to what purpose. The President does not govern the states, nor can he prevent their bold forward progress on building a climate-resilient economy.

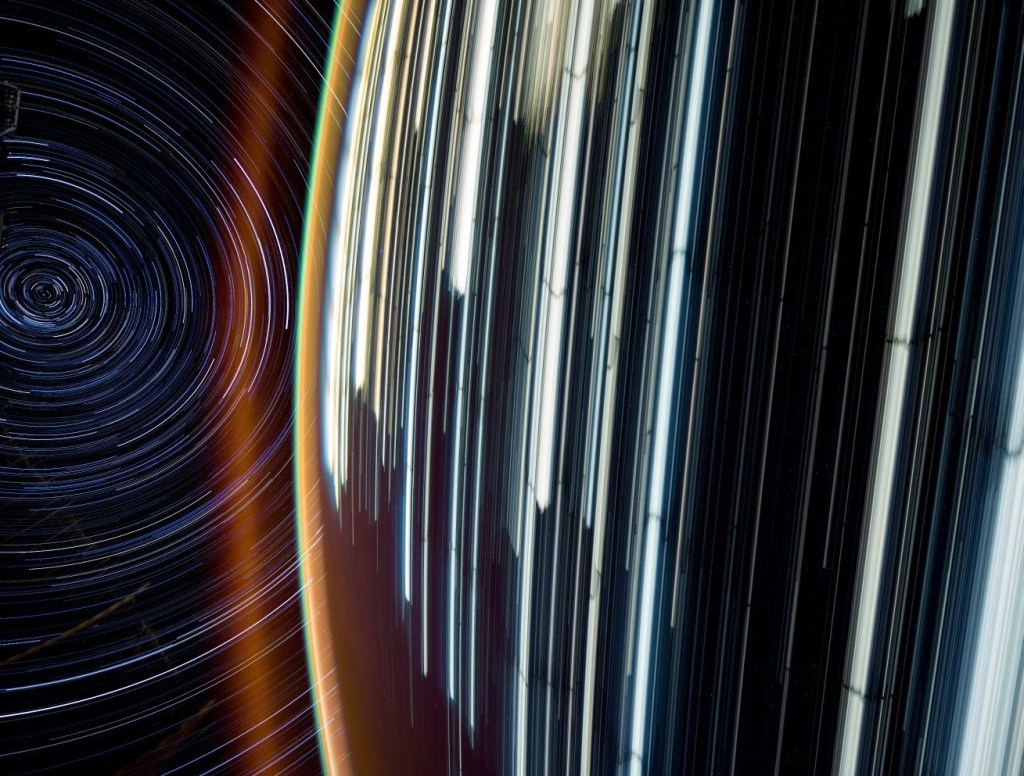

FEATURED IMAGE