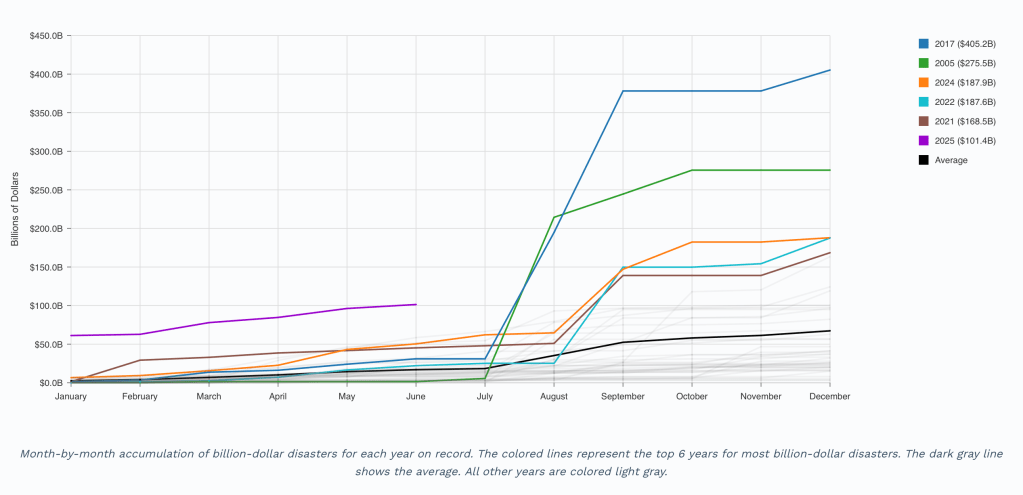

Climate change is not a future problem; it is happening now. In the first six months of this year, major disasters in the United States costing $1 billion or more set a record for overall costs. From 1980 through 1989, the US spent roughly $220 billion on disasters costing $1 billion or more. In just four months, two shock events—Hurricane Helene and the Los Angeles fires—caused such damage they will eventually cost $250 billion each.

Earlier this year, President Trump moved to end the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s tracking of billion-dollar disasters, part of its effort to study and communicate the impact of climate change on everyday lives and the US economy. That effort has now been taken up by Climate Central.

This is critically important, because without a foundation of solid, always-active, evolving climate science, weather forecasting and early warning services will be less effective, which will directly push disaster costs higher. Not only are human lives and infrastructure more at risk when weather data is flawed, lacking or late; the political leaders and institutions that have to respond to such disasters quickly lose favor. Nearly everything they seek to do after such a failure becomes much harder, both because of the disaster response spending and the reduced public trust.

Since 1980, the US has spent roughly $3.1 trillion responding to disasters costing $1 billion or more. The average over those 45 years is about $68 billion per year. The average over the last 10 years is $150 billion. The first six months of 2025, if extrapolated to 12 months, suggest an annual cost this year of around $202.8 billion. And those are present-day costs. Remember, Hurricane Helene and the LA fires will likely each cost $250 billion over the coming 10-20 years.

This is critically important information, because many everyday activities are able to happen only because businesses, institutions, and individuals, are able to buy insurance of one kind or another. Without that, underlying costs and risks would already make it impossible to afford many things we take for granted. As the pressure on insurers intensifies, the risk of everyday systems coming apart grows.

The first thing most of us will see, if we are not directly impacted by a costly climate-related event, is the increasae in prices for goods and services. Shipping gets more expensive, as road-building and maintenance becomes more expensive, as insurance gets more expensive, as demand for redundancies to guard against supply chain disruptions grows, making many other goods and services more expensive.

Once the rise in cost is baked into Earth’s climate system, it cannot easily be resolved with public spending or tax relief. This is not a standard macroeconomic consumer pricing issue; it is a structural issue setting higher costs as a background condition and limiting everyone’s options for working around those added costs. Monetary policy will have little effect, if climate disruption keeps getting worse—meaning shock-event costs and their ripple effects could become an issue for fiscal stability, even in the wealthiest countries.

That is not a quick read of the news of 2025 costs. Leading US financial regulators have found the financial system and fiscal stability are at risk:

- The Commodity Futures Trading Commission found in 2020 that unchecked climate change would destabilize the financial system and undermine its ability to support the everyday economy.

- In 2021, the Financial Stability Oversight Council issued a similar finding, warning “Climate change is an emerging threat to the financial stability of the United States.”

The International Monetary Fund has found that global subsidies for fossil fuels amounted to $7 trillion, equivalent to 7.1% of all economic activity, in the year 2022. Subsidies have continued growing, even as all countries are making commitments to reduce climate pollution.

The costs of this massive investment are widespread pollution of air and water, disruption of Earth’s climate system, which further disrupts watersheds, ecosystems, and the habitability of both rural and urban areas. The $7 trillion figure does count some of the underpricing of real-world costs, which result in public expenditures, but it does not count all of the costs of climate destabilization, or embedded costs of unsustainable practices, including use of fossil fuels, throughout our food systems.

The Food System Economics Commission has tracked $145.84 trillion spent on the costs of unsustainable food systems, since April 2016. (If you were to round 0.84 to 0.8 or 0.9, that value difference is between $40 billion and $60 billion.) As we have noted before, pollution subsidies are irrational and wasteful, and limiting the flow of quality climate data will not reduce legal and financial liabilities but will exacerbate them.

Climate denial mythology—false claims that the costs of climate solutions are higher than the costs of climate impacts, and that impacts will happen only in the distant future—have come to permeate our political discourse, even as large majorities of Americans say climate change is happening now. Self-described “fiscal conservatives” who say they want to limit government spending and sovereign debt often refuse to acknowledge the fiscal stability risk inherent in the fossil fuel investments they support.

There is no good outcome for the US economy, if the federal government continues shutting down or trying to block the flow of high-quality climate data. Policy-makers need new ways to talk about and respond to the steady and accelerating rise in climate-related disaster costs. Well-informed efforts to bolster fiscal resilience, using multidimensional value-creation insights are essential to the wellbeing of nations, regions, cities, communities, and to businesses large and small.